Motix for Neuromuscular Rehabilitation

Feb 2025 – present

I have submitted Motix for presentation at Prototypes for Humanity, which will be held in Dubai in November! Check back soon to see if Motix qualified!

this is a work in progress! updates are added weekly until this project is finalized. feel free to contact me at mouathabudaoud1@gmail.com for any inquiries, comments, or suggestions.

Background and Motivation

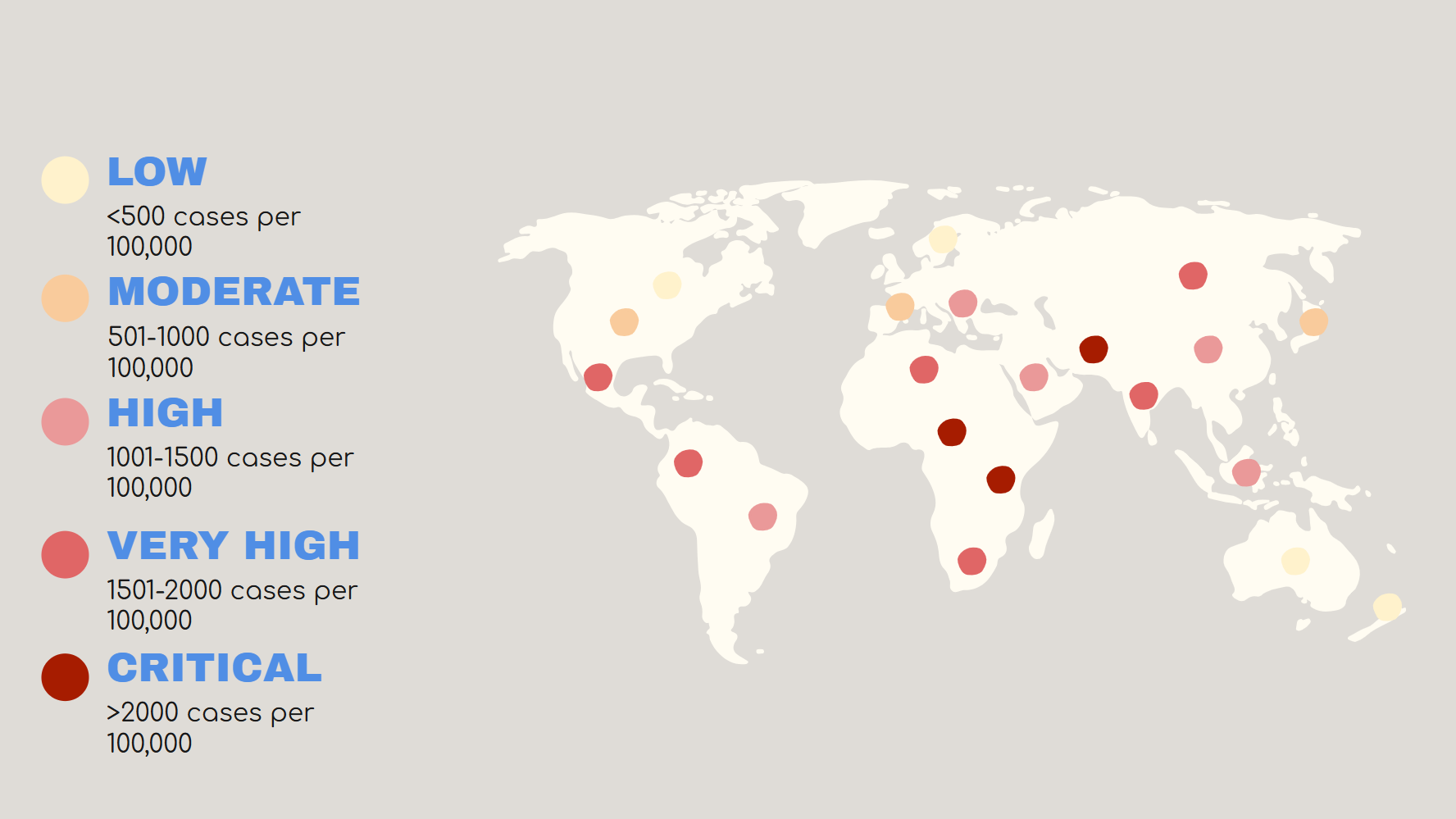

According to the World Health Organization, over 350 million people worldwide live with neurological disorders that lead to motor impairment, with $1.5 trillion dollars spent annually toward their healthcare and rehabilitation costs. In fact, the prevalence of neurological disorders is highest in underserved areas globally, as shown in Figure 1 below. This inspired me to look into the current state-of-the-art rehabilitation solutions for neurological and neuromuscular disorders.

Figure 1 – Prevalence of Neurological Disorders per Region (cases per 100,000)

As of 2025, therapy and rehabilitation options include: (i) Physical Therapy (PT) to improve strength, coordination, and mobility; (ii) Occupational Therapy (OT) to train patients in daily activities such as dressing and writing; (iii) Speech and Language Therapy (SLT) for patients with speech or swallowing issues; and (iv) State-of-the-Art Rehabilitation Systems involving robotic gait training, wearable rehab devices, and VR-based rehabilitation systems.

Traditional therapy techniques such as PT, OT, and SLT are essential for recovery, particularly for diseases like stroke, cerebral palsy, MS, or Parkinson’s. However, significant obstacles often exist in their accessibility, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Access to care is often limited by a lack of specialized clinicians, inadequate infrastructure, and high costs, leaving many patients without effective therapy options. Even when rehabilitation is available, conventional approaches can be repetitive and disengaging, making it difficult for patients to stay motivated throughout their recovery journey.

On the other hand, technologically powered systems demonstrate immense potential to revolutionize recovery for patients. Technologies such as robotic-assisted training, virtual reality, functional electrical stimulation, and non-invasive brain stimulation may revolutionize motor recovery. However, they tend to be prohibitively expensive, limited in scope, or require specialized equipment and clinics, concentrating them primarily in high-resource settings.

There’s a gap in the market for something that is affordable, user-friendly, adaptable, and can be used at home or in low-resource settings – and that’s exactly what Motix aims to provide. My goal is to help ensure that effective neuromuscular rehabilitation is not a privilege, but a universal right.

Understanding Strokes and their Rehab

While the end goal is to provide accessible and scalable rehabilitation for a broad range of neuromuscular disorders, it is smarter to start with a focused target and scale up with time and experience. As such, after reviewing the most common neuromuscular disorders worldwide, including stroke, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, I chose to make Motix initially focused on stroke rehabilitation.

This is due to the fact that stroke is the second leading cause of death and a major contributor to disability worldwide, affecting approximately 13.7 million people each year and resulting in 5.5 million deaths annually. Notably, the incidence of stroke has doubled in low- and middle-income countries between 1990 and 2016, while it has declined by 42% in high-income countries over the same period. This stark disparity, combined with the sheer scale of the problem, made stroke the ideal starting point for Motix.

In order to properly address stroke rehabilitation, it is essential to have a thorough understanding of the pathology and current state-of-the-art (SOTA) management strategies. First, we define stroke as a neurological disorder characterized by blockage of blood vessels in the brain, leading to cell death and loss of function. There are two types of stroke: (i) Ischemic strokes, in which an embolus (a clot) forms and blocks blood flow to the brian, leading to cell death; and (ii) Hemorrhagic strokes, in which stress in the brain tissue cause blood vessels to rupture. Both types of stroke have high mortality indices, with approximately 87% of strokes being ischemic in nature.

When blood flow is interrupted, brain cells in the affected area die, leading to loss of motor control, sensory deficits, and sometimes visual impairments. As a result, stroke survivors may experience difficulties with daily activities such as walking, toileting, and self-care, often requiring intensive and ongoing rehabilitation to regain independence. This is why rehabilitation is essential, as it aims to reinforce the functional independence of people affected by stroke through task oriented approaches like arm training and walking to help stroke patients manage their physical disability.

The effectiveness of rehabilitation is rooted in our body’s special “plasticity“, which is, in simple terms, its ability to adapt and reorganize in response to experience and training. As a result, due to the plasticity of our nervous system, it can be influenced by motor and cognitive training to retrieve its functionality after a stroke. This is done mainly through synaptogenesis, a phenomenon in which the brain can remodel itself by forming new linkages among neurons. Specific tasks and repetitive exercises appear to be key elements in promoting synaptogenesis, and are central to the rehabilitation of motor weakness after stroke. In fact, evidence shows that high-intensity upper-limb and lower-limb physical therapy both resulted in significantly greater improvements in motor function.

When putting all of this information together, it is intuitive to shape Motix into a tool that utilizes the exercises and specific movements targeted in physical therapy in a gamified fashion to provide the functional recovery of rehabilitation in a more fun and engaging way, allowing for higher patient motivation and adherence, and thus better patient outcomes. As such, I will be aiming to split Motix into two parts:

1. an upper-limb rehabilitation platform focused on exercises such as:

- Hand Opening and Closing

- Wrist Flexion and Extension

- Elbow Flexion and Extension

- Shoulder Rotation

- Object Throwing, Picking up, Moving, Lifting, and Rotation

2. a lower-limb rehabilitation platform, focused on exercises such as:

- Single-leg Standing

- Side Stepping

- Diagonal Stepping

- Back Stepping

- Knee Lifting

Methodolgy

Given that one of the primary objectives of this project is to provide a low-cost, gamified neuromuscular rehabilitation platform. It is essential to prioritize high-quality but low-cost materials and electronics. I am aiming to make both platforms PC and console compatible, so that they can be used as controllers for already established and loved games. I will try to resort to 3D printing as much as possible.

In this section, we can finally get technical!

(a) Lower-Limb Rehabilitation Platform

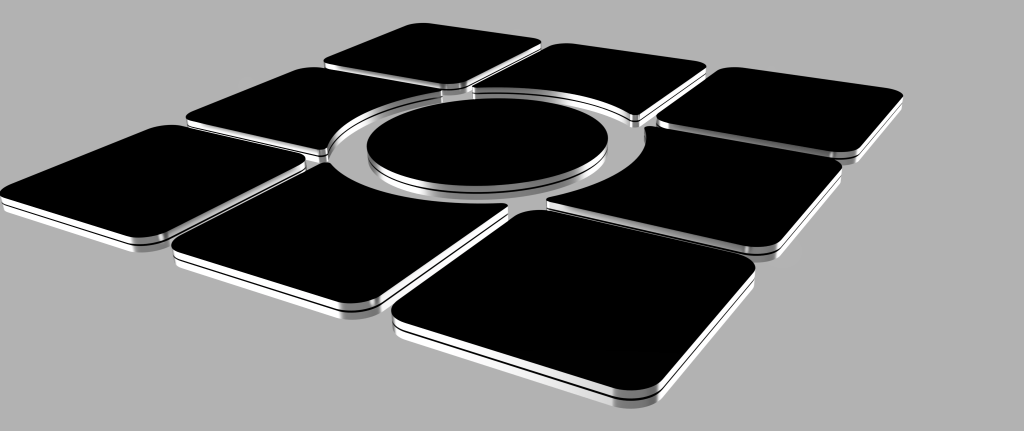

In order to build a platform that is capable of detecting user input as needed by the exercises outlines above, the platform must be sturdy enough to handle the weight of the user standing and moving on top of it. Additionally, since we aim for input from the leg, it must be equipped with a sensor that can be triggered by the foot easily by the user. As such, I am thinking of building a platform inspired by dancing arcade machines, as shown in Figure 2 below!

Figure 2 – Dancing Arcade Machine

Of course, this would not require a screen to be built as is typical in the dance machines found in arcades. Alternatively, we can use the concept of having a platform with multiple buttons to be used for gamified rehabilitation. In this way, having a grid of buttons that the user can use as input for their game allows for the integration of exercises such as side stepping, diagonal stepping, back stepping, and single-knee raises into the game, as shown in Figure 3 below. It is important to note that this might not be applicable to all games, but is a good start nontheless.

Figure 3 – Illustration of a Dance Machine-like Grid for Lower-limb Rehabilitation

Now, given that we have a concept in mind, we can start drafting mechanical and electrical designs.

(i) Electrical Design

In order to collect useful data, I want to be able to measure plantar pressure distribution data. This could allow clinicians to further optimize rehabilitation directions for faster and more efficient outcomes. The data to be collected are as follows:

- Verical Force: the force acting on the foot in a downward, vertical direction when it’s in contact with the ground. Vertical ground reaction force measurements provide insight into how effectively a patient is loading their limbs during walking or balance tasks. Improvements in vertical force symmetry and magnitude are associated with better functional recovery and are a target of neuromuscular reeducation programs.

- Center of Pressure Trajectory: tracks the path of the average pressure point under the foot during stance and gait. Differences in CoP patterns can reveal balance impairments, altered gait strategies, and risk of instability in patients with neuromuscular conditions. For example, research shows that the CoP trajectory in the anterior-posterior direction is significantly altered in neuropathic and post-stroke gait, reflecting underlying motor control issues.

- Peak Pressures and Pressure Distribution: peak pressure is the highest pressure exerted in a specific area, while pressure distribution encompasses the overall pattern of pressures across the foot. In people with stroke, abnormal pressure patterns, such as increased pressure on the lateral heel or reduced pressure under the forefoot, reflect common issues like weakness, spasticity, and inefficient push-off.

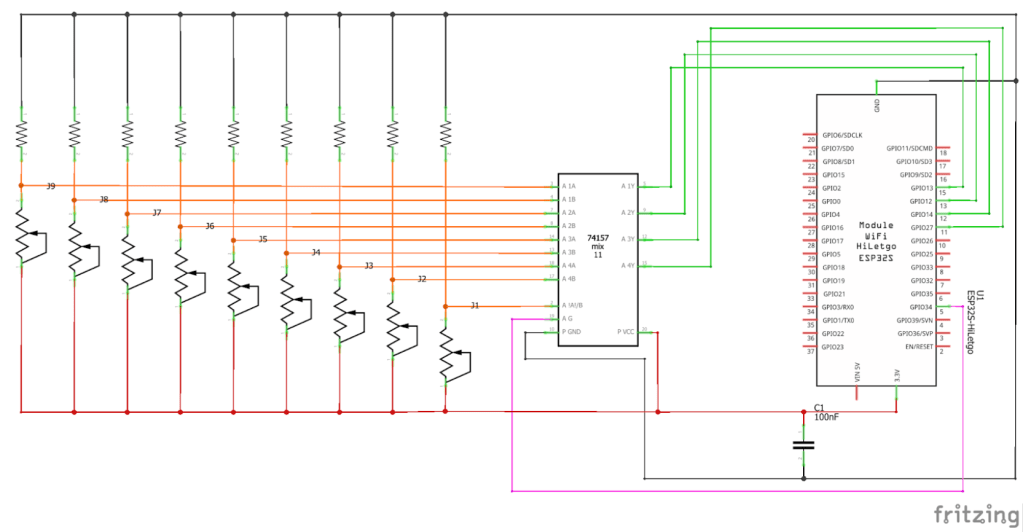

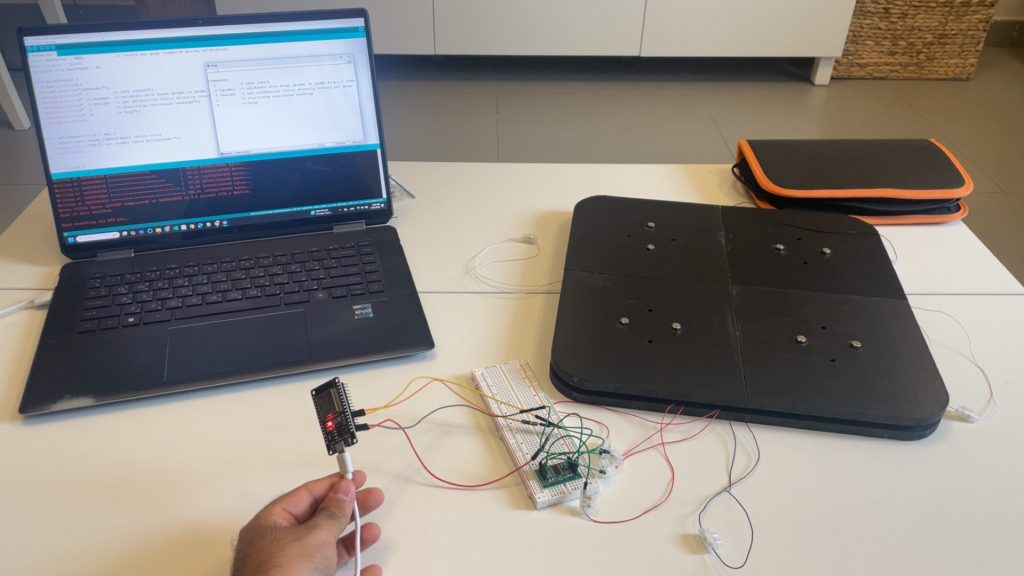

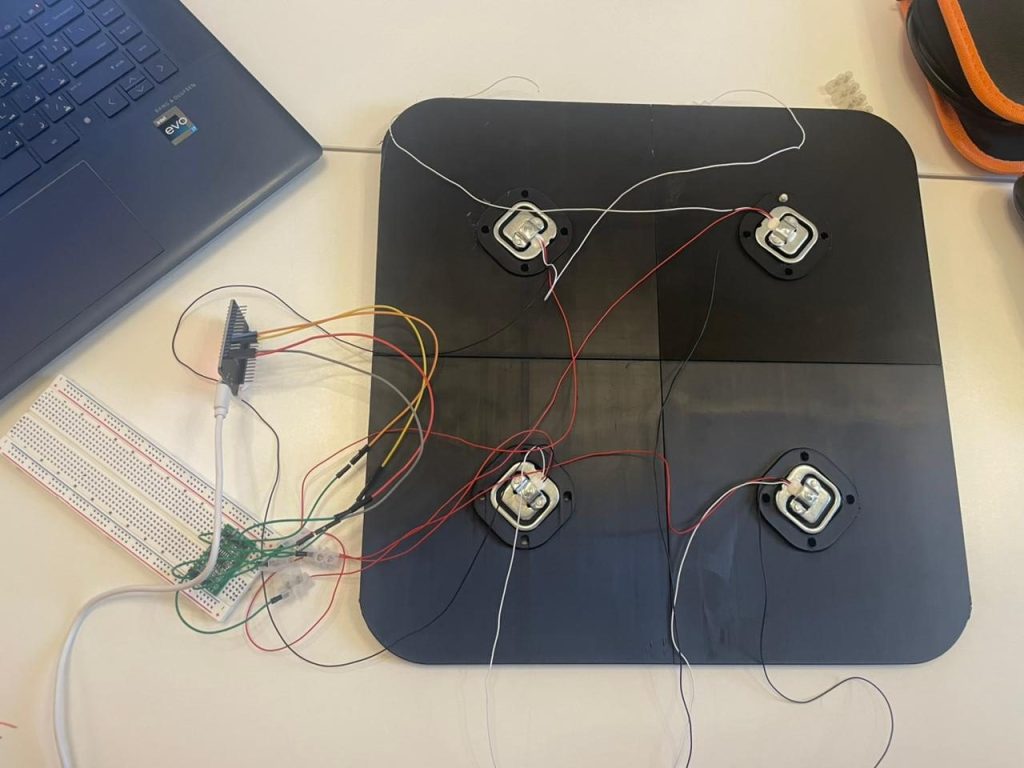

While this data requires extensive and detailed sensor integration, it is possible to collect and is highly useful. However, since we are at the initial stages of the project, we will start off with vertical force only, and move our way up to measure the remaining data. This can be done using standard load cells (typically used by bathroom scales) or force-sensitive resistors. I will be testing both and seeing which is better when possible. In order to allow for communication with a PC/ gaming console, I will be using an ESP32 circuit board as the mictoprocessor for the lower-limb platform, as it has built in bluetooth integration. The figures below show different iterations of the electrical design on Fritzing:

Figure 4 – Electrical Circuit Design – Lower-limb Platform – Version 1

Figure 5 – Electrical Circuit Design – Lower-limb Platform – Version 2

I like color coding my circuit designs for ease of readability and adjustment. If you have any questions about the current designs, feel free to contact me!

(ii) Mechanical Design

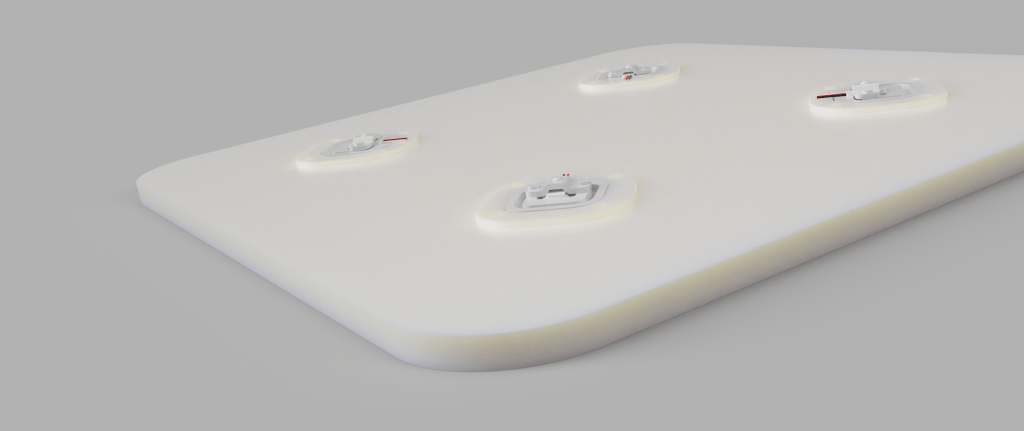

In order to properly design a mechanically functional platform that can be used for high-quality user input and maintain constant load, I opted to draft a design on Fusion 360 to be able to conduct finite-element analysis studies. In Figure 6 below, I present simple renders of the mechanical design, whereas Figure 6 (a) shows a lower plate with embedded load-cells, while Figure 6 (b) shows a render of the entire lower limb platform.

Figure 6 – Lower-limb Platform – Mechanical Design Renders

- Industrial Schematics

For a more detailed representation of my design, I have provided industrial 2D schematics of my design for the top and bottom plates below. In the designs, I included a set spaces to hold all 4 components of the load-cell for each platform while maintaining minimum thickness and maximum strength.

- Finite Element Analysis

In order to validate the soundness of the mechanical design, I performed simple Stress and Displacement Analysis studies to make sure the platform can hold sustained effort from the user. Videos 1 and 2 below show the result of the FEA studies, proving (simplistically and preliminarilly) that the each platform should be able to sustain consistent 120 kg load (which is exaggerated for the purposes of this study).

Video 1 – Lower-limb Platform – Stress Analysis

Video 2 – Lower-limb Platform – Displacement Analysis

- Prototype 1

In order to test my design, I 3D-printed a prototype of the lower limb platform using PLA. The prototype is shown in Figure 7 below.

Figure 7 – Lower-limb Platform – Prototype 1

- Software Implementation/ Code

The first draft of my code is shown below. This still needs to be finalized and optimized!

#include "HX711.h"

const int LOADCELL_DOUT_PIN = 4; //DT

const int LOADCELL_SCK_PIN = 16; //SCK

HX711 scale;

float calFactor = NAN; //counts per gram

bool running = false;

unsigned long lastPrint = 0;

void printHelp() {

Serial.println();

Serial.println("Commands:");

Serial.println(" t -> tare (zero)");

Serial.println(" c <grams> -> calibrate with known weight in grams");

Serial.println(" f <value> -> set calibration factor directly (counts per gram)");

Serial.println(" r -> start/stop continuous readings");

Serial.println(" h -> help");

Serial.println();

}

bool waitReady(uint32_t ms) {

if (scale.wait_ready_timeout(ms)) return true;

Serial.println("check wiring or power");

return false;

}

void setup() {

Serial.begin(115200);

delay(500);

Serial.println("trial");

scale.begin(LOADCELL_DOUT_PIN, LOADCELL_SCK_PIN);

if (!waitReady(2000)) {

Serial.println("continuing...");

}

//start with scale factor = 1 so get_units() equals raw counts after tare

scale.set_scale();

Serial.println("tare... remove all weight");

delay(1500);

scale.tare();

Serial.println("tare done");

printHelp();

Serial.println("calibrate with 'c <grams>' or set factor with 'f <value>' before running 'r' for grams");

}

void handleCommand(const String& line) {

if (line.length() == 0) return;

char cmd = line.charAt(0);

if (cmd == 'h' || cmd == 'H') {

printHelp();

} else if (cmd == 't' || cmd == 'T') {

if (waitReady(2000)) {

scale.tare();

Serial.println("tare complete");

}

} else if (cmd == 'f' || cmd == 'F') {

// f <value>

float f = line.substring(1).toFloat();

if (f != 0.0f) {

calFactor = f;

scale.set_scale(calFactor);

if (calFactor < 0) {

Serial.print("negative factor detected; using "); Serial.println(calFactor, 6);

} else {

Serial.print("calibration factor set to "); Serial.println(calFactor, 6);

}

} else {

Serial.println("usage: f <factor>, example: f 471.497");

}

} else if (cmd == 'c' || cmd == 'C') {

// c <grams>

float known_g = line.substring(1).toFloat();

if (known_g <= 0) {

Serial.println("usage: c <grams>, example: c 500");

return;

}

Serial.println("empty the scale; re-taring...");

if (!waitReady(3000)) return;

scale.set_scale();

delay(1000);

scale.tare();

Serial.println("place the known weight and wait...");

delay(3000);

if (!waitReady(4000)) return;

long reading = scale.get_value(10);

float f = reading / known_g;

if (f < 0) f = -f;

calFactor = f;

scale.set_scale(calFactor);

Serial.print("calibration factor = "); Serial.println(calFactor, 6);

Serial.println("calibration done");

} else if (cmd == 'r' || cmd == 'R') {

running = !running;

Serial.print("running = "); Serial.println(running ? "true" : "false");

} else {

Serial.println("unknown command. press 'h' for help");

}

}

void loop() {

if (Serial.available()) {

String line = Serial.readStringUntil('\n');

line.trim();

handleCommand(line);

}

// Continuous readings when running

if (running && millis() - lastPrint >= 300) {

lastPrint = millis();

if (waitReady(500)) {

// If not calibrated yet, show raw counts

if (isnan(calFactor)) {

long raw = scale.get_value(10);

Serial.print("raw: ");

Serial.println(raw);

} else {

float g1 = scale.get_units(5);

float g2 = scale.get_units(15);

Serial.print("grams: ");

Serial.print(g1, 2);

Serial.print(" | avg(15): ");

Serial.print(g2, 2);

Serial.println();

}

scale.power_down();

delay(5);

scale.power_up();

} else {

Serial.println("sensor not ready...");

}

}

}(b) Upper-Limb Rehabilitation Platform

I will be working on the upper-limb platform soon. Check back soon for more updates!